Standards committees, ask your users

A while back I tweeted that users and authors, to the contrary of the popular belief, are less important than browser implementers and spec writers in standards committees. I really think it is the case, and I’ll care to explain why in this blog post.

Implementers have the executive power

In the real world, implementers (Google, Mozilla, Apple, Microsoft…) are at the top of the decision chain.

Because, at the end, only them will decide if they are going to support a feature or not, they don’t really have to care about what’s said by standards committees, advisers and communities.

If you ask one single example of where implementers desires overruled both spec writers, authors and users benefits, check out the video format discussion.

Because it was the best format available and was benefiting user’s experience and battery lifetime, Apple and Microsoft supported very early the H264 video format. However, this format isn’t patent free; authors of commercial websites should pay royalties to use the format. Mozilla and Opera decided they would not support this format in their browsers.

At the end, authors have to include the video in at least two formats to be compatible with all browsers; some authors don’t care to do it and therefore, sometimes, you encounter as user a video you can’t play on the web.

At the time, I proposed to add a normative note forcing every browser to support both formats, since both were free to decode, and let authors decide which one they wanted to support; this failed for philosophical reasons. Really, implementers are the king of the web.

Authors need to scream to get heard

However, the implementers oligarchy is not the only problem the web community face. Another very concerning problem of standards bodies is their lack of feedback tools.

Most of the time, it’s nearly impossible for authors to give feedback on the current advances of a working group.

Well, public mailing lists do exists, and they are really nice (at least for some working groups). However, very few people know that those mailing list exists (probably a good thing as they should stay focused) and it’s difficult to get heard there.

When you’re making proposal, the first reflex of the members of the group is usually to ask you to make a specification.

However, you will find very few guidance on how you should write specifications; you really need to know the standards committees habits to make something usable.

Also, writing specs takes a lot of time and requires good writing skills. Not every creative web developers willing to spend a bit of time to make the web a better place have both. As a result, too many good ideas die before they were even considered.

Yet, making a specification is not the most difficult thing you’ll have to do.

Even when people get together and craft a draft specification (let it be the <picture> tag or the CSS custom properties), they are generally mostly ignored by the group members; sometimes the discussion continues as if they weren’t there and didn’t even spend any minute of their time making the specification.

To get a specification break even, you need to build up the buzz. Creating the buzz around a specification which has no implementation is really challenging. Also, you need to maintain the buzz for a certain amount of time, which is really difficult if you are not in the public figures of the web.

As a result of this cumbersome process, an important slice of the motivated people which have something to share leaves the communication channels frustrated.

The need for an unified proposal repository

Right now, what’s preventing standards committees from getting the feedback they need is a centralized experience where people can report ‘issues’ of the open web stack, objectively compare and vote for solutions.

An issue can be anything someone would like to do but which is not possible (or awkward) to do using current technologies. I guess a certain amount of beginners would post bugs for already-existing features, but it is a noise I think we can keep low by managing registrations on the website through an invitation process only. Also, since web developers can vote for issues and solutions, false reports could be identified quickly by crowdsourcing.

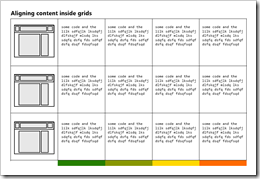

When a bug is identified, people can add uses-cases. Uses cases would generally consist into an image of the desired rendering and a small HTML code snippet. The objective of use-cases is to show what a feature is all about, and what kind of problems it should solve.

As soon as use cases are identified, spec writers, implementers and authors can provide solutions to the use cases, in the form of a small description and a code snippet using their proposal for each provided use case.

I also envision that authors may want to highlight advantages of their proposal by adding “attributes” to solutions like “stability”, “ability to draw complex geometries”, …The end result would be a bit like the PC comparator tools you can find on the web and especially on good shop websites. Everybody can select its own criteria, compare the solutions. Everybody can participate.

Authors and implementers could then vote on proposed solutions, plus comment and edit them in a collaborative way.

At some point in time, the call for proposals would be frozen and standards committees can decide during a telcon or a face to face which proposal they want to support or bring into a specification, mostly the way they do it now.

The only big difference is that ideas would have grown in a public world, would have been refined, compared and that the final selection would not be under the responsibility of the spec writer (which usually make a wiki page about the proposals he like the most).

A tool can only work with the support of committees

For such a tool to work, it would have to be supported strongly by the committee itself, or it will quickly die, because proposals appearing there would never or too few make the cut in real WG discussion.

I hope that, someday, something like this will happen. And not just a simplified version for ECMAScript which you should have a look at.