The future of web innovation

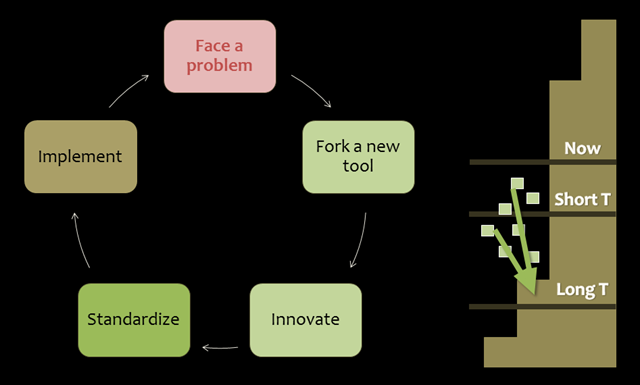

Back in early 2010, I made a lightening talk on how I thought a new kind of innovation process started to drive the web forward. Today, I think this model is becoming more and more the predominant model of evolution of web standards.

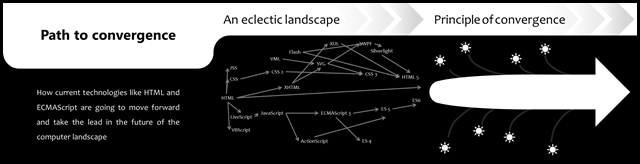

In the last 15 years, the web stack (HTML/CSS/JavaScript) has been a source of inspiration for numerous of other technologies. Every organization was developing a solution that expanded the web model (Mozilla and XUL, Microsoft and XAML, Adobe and Flash) which was attempting to solve a problem the current browsers were unable (or inefficient) to solve.

However, in the long run, the web adopted the best parts of each one of them and incorporated them in ‘the web standards’ (CSS Flexbox from XUL, CSS Grid from XAML, SVG from VML, HTML Canvas from Flash and so forth).

This is a model I called back then the “Principle of Convergence”.

The reason why those extensions to the web model, called plugins, had to appear is really simple: there were some developer’s needs that the available web APIs could not satisfy. Those plugins were a good thing, because they helped developers to provide better content to their users.

But there was also the drawback that those plugins were not available on all platforms, creating compatibility issues. Additionally, most of them are not aging so well but are still important features to support for compatibility reasons nonetheless. In fact, nowadays, there are so many platforms it’s even not possible to maintain existing plugins for all of them (even Adobe was forced to stop supporting Flash on mobile platforms).

At some point, the features provided by those plugins got added to the web standards, one by one, and most of them are now a thing of the past. But they refused to die, and were not done in a forward-compatible way. I take no risk when I say that the era of plugins is now arrived at a dead end, but their death is slow and painful.

Meanwhile, the developer’s needs will not stabilize anytime soon, the Computer Science field is way too young for that. That means the innovation process by extension is not going to stop anytime soon. Libraries like jQuery remind us it’s still not easy enough to work with the native DOM libraries for most developers. So, what should we do instead of making plugins? How can we solve problems in the short term via extensions?

An extensible web for experiments and edge cases

If it is not possible to produce extensions to the web via plugins, it means we need a way to create extensions directly inside the web. Historically, this was nearly impossible due to three major factors:

- JavaScript was an interpreted and very slow language. Nowadays, JIT code is nearly as fast as standard native code.

- The native APIs on which you could construct on were too high-level and not optimized enough. This is not the case anymore with powerful APIs such as CSS Custom Shaders and HTML Canvas.

- When you wanted to add features to an element of the page, you messed up other's features with the other’s features (i.e. conflicts issues between extensions). This is certainly still the case at this time, but isolation-enabling features like Web Components, Private Names, Data Attributes and CSS Custom Properties make it possible for multiple extensions to coexist in a stable way, and often without even seeing each other.

As we can see, things are in a much better situation now. However, not everything is nice in the 2012 web world. A lot of work still needs to be done in order to allow clean, efficient and stable Forward Polyfills to the web stack.

This is why we launched the Extensible Web Community Group at W3C. We hope to create an environment that plays nicely with polyfill authors, and that allows us, developers, to have our imagination as our only limit when using the web, and not the browser compatibility issues ![]()

At the Extensible Web CG, we want to create simple & forward-compatible JavaScript extensions to the web called prolyfills. Those small extensions allow innovators to propose solutions to issues faced everyday by authors without asking for clumsy author code and without going through the pain of standardization immediately, but with the security of a forward-compatible model that can only become faster over time, and should never break.

Just like anybody can craft a new word in the English language and use it in his own talks. After that, standardization committees can have a look at some popular or important prolyfills and standardize them, the same way a popular word finally made its way to the Oxford dictionary.

If you want to see how we progress in our work, or would even like to participate in the discussions, please join us!

Annex A: Why this model will work

An important consideration to have when you’re proposing an innovation model is to have a look at the reasons why the important actors (big software companies) will embrace your model, i.e. what’s the advantage they get out of it (let’s face it, we live in a pragmatic world).

Firstly, they can leverage based on their innovations. When they introduce new features to the web, they can develop tools that will “convert” a nice code into a standardized code that can run on all platforms, the same way SASS compiles to CSS or TypeScript to JavaScript. So, they have a benefit from being the first mover because their tools and workflows are getting better as a result. Also, they don’t have to wait for others to care about their issue to market their new solutions.

Also, there’s a strong incentive in standardizing the other’s innovations if you feel they’re important: by standardizing, you make sure any editor can produce the same clean code and, as such, you put to an end to the “first mover advantage”.

Standards committee will also benefit from past implementation experience when making decision, and have less “pressure” on getting work done quickly, so they can make sure to make the things right instead of just getting them working.

And if standardized solutions are nicer, this is a benefit for the casual web developer, too. It’s an end to the time you need to understand why features were implemented in such a bloated way, you can safely download new libraries via a package manager à la NuGet/Eclipse/etc and choose the best ones, without fearing compat issues between those.

Last but not least, this model enables occasional developers and hobbyists to develop custom solutions to solve their own issues that nobody except them will ever care about (in a foreseeable future).

Annex B: Proof this model is already in use

Software corporations having a browser have understood that implementing things in their browser only was not a good way to innovate anymore. So, they’re trying to do their best to make their latest innovations cross-compatible, providing polyfills when needed.

Also, software corporations that don’t ship any browser, like Adobe, make already use of prolyfills to improve their tool chain (Appache Cordova/PhoneGap anyone?) and they continue to use this model in the future.

Annex C: How this relates to Windows 8

This discussion between plugins and native extensibility lead me to think about the approach chosen by Microsoft on Windows 8. The new Modern UI applications are not allowed to accept plugins. This is a major break since the model that has been in use until now on Windows where plugins via OLE were seen as a good thing.

In fact, Microsoft want to replace “local plugins” by “global plugins” where a plugin expresses via a contract the input arguments he expect, so that the same plugin can become usable by more than one application instead of being limited to one for which it was built for.

This is the idea behind the “Share”, “File Open” and “Search” contracts in Windows 8 and this is something that will likely expand even more in Windows 9, making the console/terminal a thing of the past for even more usages (since you’ll be able to chain graphical applications in an efficient and “type-safe” way).

Also, the OS can “guess” the most likely next application in the chain by analyzing your own usage (or by doing global stats) to help you use the good tools with ease.

The same idea will likely grow on the web as a form of Web Intents (but it’s arguably more difficult to make the specification progress in an environment where not everybody want the same contracts).